[ad_1]

The Boy and the Heron, which may well be the Studio Ghibli co-founder’s ultimate movie, is extra of a daring reinvention than a somber farewell.

The primary sound in Hayao Miyazaki’s new film, The Boy and the Heron, is an air-raid siren, heard over a display screen of black that temporarily explodes into tumult and destruction. It’s 1943, and a firebombing has set a Tokyo health center ablaze, killing the mum of 12-year-old Mahito Maki, the film’s protagonist. Miyazaki depicts the incident with nightmarish bluntness: Mahito operating towards the development, then being held again as flames eat all the display screen, overwhelming any probability of saving his mom.

The loss of life is a second of stunning fact from a filmmaker and an animator who, for many years, has blurred actual lifestyles with delusion, development a name as considered one of cinema’s major masters of dreamlike imagery. The scene additionally has a jarringly autobiographical edge: Even if Miyazaki’s mom didn’t perish in International Battle II, his early youth used to be outlined by way of the struggle, and he needed to evacuate his house on the age of three when it used to be bombed by way of america. The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s first movie in 10 years, and given his age—he’s 82—it may well be his cinematic swan tune (although he has proved extraordinarily excellent at failing to retire). However what’s maximum shocking is how bold its storytelling feels. Even now, the Studio Ghibli co-founder is discovering new tactics into his narratives.

Many of the film’s first part is solidly planted at the flooring: After the loss of life of his mom, Mahito strikes to a carefully habited nation-state property along with his father, who has married his mom’s more youthful sister. There, he struggles to get used to his courting along with his “new mom,” Natsuko; is bullied in school; and is fussed over by way of a gaggle of comically aged maids (the only component within the movie’s early acts that appears like vintage Miyazaki). The despair tone of those scenes resembles the outlet act of My Neighbor Totoro, most definitely Miyazaki’s best-known paintings, which additionally follows youngsters exploring bucolic bits of nature whilst wrestling with the absence of a father or mother.

In The Boy and the Heron, Mahito does no longer meet pleasant forest sprites; as an alternative, he crosses paths with a menacing grey heron who speaks to him in a guttural growl and demanding situations him to discover a crumbling tower at the property’s grounds. As soon as there, the tale shifts into one thing extra standard for Miyazaki, as Mahito enters a delusion international the place, the heron asserts, he might be able to see his mom once more. When he starts to navigate a dreamscape full of speaking birds, transferring landscapes, and mysterious, ghostly creatures, it’d be simple to assume the movie used to be about to settle into recognizable whimsy.

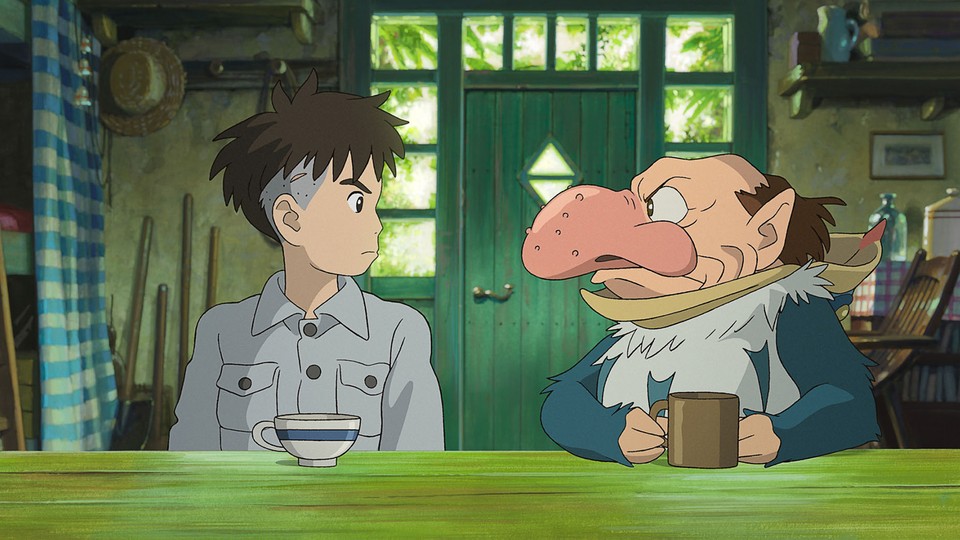

Now not such a lot. The Boy and the Heron trades in all the imagery Miyazaki excels at, however makes use of it to inform a darker story of affection and loss. Whilst Mahito strikes from realm to realm, he’s each helped and adverse by way of the heron, who seems to be a gnomish creature of mischief dressed in an elaborate gown. The dreamy good judgment of the movie ceaselessly feels out of keep an eye on: Mahito is with a warrior pirate queen at one second, then contending with a bunch of marshmallow-shaped bubble creatures who supposedly constitute unborn human souls, then doing combat with a kingdom of big parakeets. And he’s occasionally accompanied by way of a tender magical girl named Himi, whose function turns out deliberately opaque.

For a excellent chew of the movie, it’s arduous to grasp if all of those disparate threads will come in combination. Miyazaki’s earlier movie, 2013’s unbelievable The Wind Rises, used to be additionally considered one of his maximum mundane works, a unfastened biography of the inventor of Japan’s 0 warplanes, which shaped the spine of the rustic’s International Battle II air power. Most likely, I believed, The Boy and the Heron would finally end up feeling like a counterpart—an inscrutable typhoon of strangeness to observe that sobering realism. However on the finish, the puzzle items start to come in combination. Himi’s identification turns into clearer, and Mahito’s true undertaking on this measurement is printed: to satisfy its inventor, a wizened outdated guy wrestling with the legacy of where he’s created.

It’s simple to mention that this “Granduncle,” along with his tangled grey hair and thousand-yard stare, is Miyazaki himself—an outdated grasp reckoning with what he’s going to go away at the back of. (The inclusion mirrors Martin Scorsese’s self-insertion on the finish of Killers of the Flower Moon, the place he overtly mirrored at the function of telling true-crime tales for an target market’s leisure.) I’ve been brooding about different readings, however whether or not or no longer the director is drawing himself on-screen, it sooner or later turns into evident what The Boy and the Heron is ready: the tactics we come to phrases with loss, and the way perfect to take into consideration the reminiscences that arrive after an ideal departure. What’s vital is that the movie is alive and wakeful with power. That is no marble mausoleum of a film—it’s extra of a daring reinvention than a somber farewell.

[ad_2]